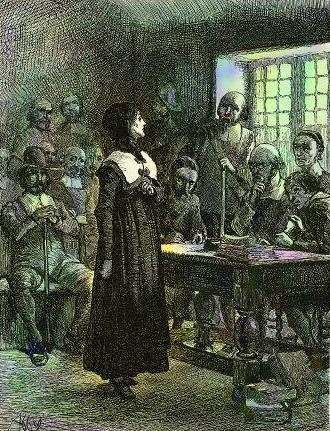

The first section of the book I am planning is called "Monster." It focuses on Mary Dyer giving birth to the "monster," the deformed, stillborn female infant, in 1637, which is what thrust her into public view -- and must surely have had some kind of lasting effect on her psyche (the birth itself, and the subsequent publicity). It will cover her early life (mostly unknown), and what happened with Anne Hutchinson and the so-called Antinomian Controversy (so much known, it's going to be a challenge finding a fresh and accurate but non-academic way to review all of this for general readers; summarizing is so boring, and it's hard for me to know what people need to know and what they don't outside an academic context). Somehow within this I need to start interweaving the personal and political themes I want to explore in the book, although it feels like most of the concrete memoir pieces I have in mind fit better in later sections -- it's my growing-up that would fit in this part chronologically, and there isn't too much I want to say about that as it doesn't really fit my themes.

There is a hefty amount written about the meaning of "monstrous births" in the early modern world, relevant to both Dyer and Anne Hutchinson (who had her own in 1638), in addition to articles directly about them. And there is vastly more about the larger topic of women and monstrosity, deviant women as monsters, etc., which I have begun to research. It's a little overwhelming -- but I'm reminding myself this is one element of many and I'm not doing an exhaustive study. It's hard to look at academic writing and realize that is not what I am trying to achieve, not to feel outdone by it.

While I was looking around online last week I came on the poem

"Monster" by Robin Morgan (1972), also the title of her first book of poetry. I couldn't believe I'd seemingly never read it before, and it struck me forcefully. It seems the equivalent of not knowing Adrienne Rich's

"Diving into the Wreck," say, a poem written around the same time I have known as long as I can remember and have taught too. (I can see how the earlier me at least would see Rich's as a "good poem" in ways I would not have found Morgan's, so maybe I did encounter it long ago and dismissed it. But now I find it fascinating in ways that have very little to do with poetic craft.) I really wanted to write about the poem as a way of thinking through the resonances with my themes I was feeling so strongly. So what follows is what I ended up writing (I get to the poem about halfway through). It pulled in a lot of ideas I already knew would be in this section in some form. I wrote it with the book itself in mind, not as a blog piece, but now I realize that I am covering too much too fast, I have to slow down and treat the elements more fully across essays in the section.

It is pretty wild and extreme, and rough and raw. I am trying to let myself go that way in my writing, otherwise I can't make this the book I want. Do I literally believe everything I have written here? I don't know. At any rate, it captures of the hybridizing of many elements that is what I am striving for, although I probably won't often cram them in one section like this. The book is not only about Mary Dyer, although it uses her as a touchstone.

In the beginning I take issue with some things in another section I drafted recently; all that will probably change, but it doesn't seem worthwhile to spend more time figuring out another way to begin right now, before the real pieces are in place.

****************************************************************

No, what I wrote earlier about being a monstrous woman like Mary Dyer was all a lie. Or at any rate, too staged. The pain you can display is not the pain you fear.

I have never been other than relieved not to bear children, and never to have been expected to.

I have felt strange all of my life, but I mostly hungered to understand. To figure out what I was meant to do, and be – the way believers wait to discern the Lord’s will, as I did once, waiting in the Light, but even after I no longer knew what that meant I still sought truth, at least until the years it was too hard to seek anything but dailiness and small pleasures. Only on occasion did I feel grotesque, misshapen. It was who I had always been, so how could I be afraid? Or if I was afraid, it was only of the possibility of being alone forever. Which by the time it seemed to be the case I could recognize as something I must in part have chosen, so it was no longer fearful.

Whatever Mary Dyer felt in herself, in her secret heart, was one thing. What she was made in the eyes of others was something else.

Awful as it was not simply to be banished with her husband but to have her horrors exhumed and anatomized in text after text, maybe in a strange way that made it easier for her. They made her a monster early and certainly, and it could not be unmade. She had crossed gone through a door in the world and could never go back. No matter what life she lived she would always be the woman who had the Monster. And that across two continents. In Portsmouth and Newport, indeed, she could live as a prominent man’s wife, a more dramatic victim of outrages most everyone thought they shared. There, I imagine, the horrible accounts of what had come from, refreshed again and again in new publications, could be muted and blocked. Across the red line, though, she would always be something else.

That thing never happened to me, or anything like it. Like Mary I am privileged. Like her I know how to behave. And my difference made me silent, made me hang back, made me fear incursion, and any kinds of wildness that would take me out of myself, unless I was pursuing them carefully and with knowledge. In my entire youth I did not do one single thing that would make me talked about, that would upset my parents or displease my teachers. Nothing monstrous has come from me. Yet.

And then, in the prestigious women’s college. We were all smart, all outspoken, all feminist more or less. The oil portraits along the halls were largely of women worthies, many of them lesbians and spinsters. We quoted a founding mother’s saying, Our failures only marry, gleefully wrenching it from one sense to another. Some of my classmates were angry, radical; they objected to reading books by male authors in English senior seminar. I didn’t get it. What did I have to be angry about? I only wanted to understand why I was solitary and strange. But we all expected at some level to go on to great achievements, and love, and power. Women were winning, weren’t they, and the new world was ours. (And of course virtually all the radicals did marry, and often men. I have marveled at that over the years. It feels like only a few of us became stranger as we aged, and who would have guessed that one of them would be me.)

Being safe doesn’t feel necessarily feel like conformity, that’s the thing. It doesn’t mean just being good Christian girls or obedient wives. It can feel like achievement, like not screwing up, like aspiration. I could tell you so much about the pleasures of being a good daughter. Of getting the highest grades. Summa cum laude insignifique nota, that’s what the ancient language handwritten on my diploma says about me. Highest honors, and I never stopped clinging to it. But I was afraid to try to be a writer, or not ready, so I went to graduate school.

I recognize that I inhabit categories that some find monstrous. Jew. Lapsed Quaker. Lesbian. Woman without mate or children, with a houseful of cats. College professor, even (since that seems to have become in some sectors, disorientingly, an occupation of moral and political deviance). Questioner of many norms, the ubiquity of marriage included. But in the life I live, most of these things are invisible. What people see: well-behaved middle-aged single lady, who teaches at the local university, owns her own home and walks her dog. Friendly but reserved. Many forms of privilege and perhaps just luck or happenstance as well keep me insulated from experiencing the costs of belonging to these categories.

So long as I keep my thoughts to myself. Those, not anything that comes from my body, are what would make me a monster. Would make people talk back to me, talk about me, in ways that are terrifying.

In graduate school, the brilliant and radical young woman professor said to me, in a context now lost: “It’s important to be a woman with a mouth.” I have been thinking about that for thirty years. Measuring myself against it. I know most of my words have been swallowed. For a few years in that time I pretended to be a prophet. Other than that I have not known how to speak, mostly, other than around the edges of things.

You have to know what your truth is. You have to be willing to share it. You have to be willing to turned into a monster by those who oppose you.

Now, in the age of social media, to be a woman with a mouth is to face a full-on verbal assault of trolls and bots, calling you every name, defacing your image. Doxxing you. Like the women who gave birth to monsters passed from tract to tract, only infinitely faster and more intimate. Hatred unleashed, the power of words and representation to demonize and dismiss and seek to silence.

The thought of being one of them makes me sick with fear.

The brave are not silenced. These, too are my heroines, the women with the courage to face this, in life and online. It seems to me to require as much courage as a martyr going to the scaffold, and still more, as it must be renewed over and over daily. What gives them the courage? The women who have the inner resources. Or the intimate sustenance. Or the sustaining tribe of supporters. Do they believe in their resistance as much as the martyrs believed in God? I tell myself, I am almost alone in the world these days, who would hold my hand and love me through such an assault? Who would be my tribe to encourage me? It does not mean I am worthless if I know my limits. If I cannot yet be one of them. If I have a different calling.

If they are going to call me a monster, I can only face it for my truest words.

To find my truest words, I must be willing to face the monster, despite the fear.

Researching this section, I came on a poem that incalculably I seem never to have encountered before (or if I did, it was long ago and it left no impression): Robin Morgan’s famous “Monster,” written in 1972 in the height of second-wave feminism. It is angry, discursive, reflective, not lyrical or metaphorical the way I have liked my poetry to be. A poem that starts out addressed to men, but addresses the speaker’s self as well, and all women; searching to connect, disorderly, harsh, like something out of the seventeenth-century tract wars.

Listen, I’m really slowly dying

Inside myself tonight.

And I’m not about to run down the list

Of rapes and burnings and beatings and all the other crap

You’ve laid on women throughout your history

(we had no part in it – although god knows we tried) . . .

If enraged frustration is what moves the poem, its title and occasion springs from the speaker’s encounter with her young son, one that makes me visualize not whatever program she refers to, but an early modern illustration, part of the print culture of gynecology, anxiety over women, monstrous births:

But just two days ago on seeing me naked for what must be

the three-thousandth time in his not-yet-two years,

he suddenly thought of

the furry creatures who yawns through his favorite television program;

connected that image with my genitals; laughed,

and said, “Monster.”

The female genitals as monster: the missing link between monstrous births and monstrous women, if we needed it.

You feel the anger and near-hopeless resignation at what persists in Morgan’s words, and yet such feelings are twinned by desire, by an erotics that is of the spirit rather than the body, a wildness of longing:

I want a woman’s revolution like a lover:

I lust for it, I want so much this freedom

this end to struggle and fear and lies

we all exhale, that I could die just

with the passionate uttering of that desire.

When I read this, I think about what it means to love things that aren’t people. I do not think Anne Hutchinson or Mary Dyer were feminists in any sense that it is useful to pursue, but when I read these lines of think of the desire for transcendence and freedom that infused what they believed. Not to struggle, wondering, searching for signs of grace without enough doubt and humility to validate them. Wanting to find the change, the power, that would transform you into fulfillment, at one with the most beautiful thing you can imagine, dancing “all alone and bare on a high cliff under cypress trees. . . .” And so they were called antinomians and libertines for believing in the erotics of free grace. Of receiving naked Christ, as John Winthrop scornfully put it. That hunger – and the belief that it could be satisfied – was what made both women and so many others into monsters, needing to be banished. It was just that Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer took it a step further to become emblems of error, manifesting it with their bodies: as Thomas Weld wrote, for looke as [Mistris Hutchinson] had vented misshapen opinions, so she must bring forth deformed monsters; and as about 30. Opinions in number, so many monsters; and as those were publike, and not in a corner mentioned, so now this is come to be knowne and famous all over these churches, and a great part of the world.

Morgan’s poem goes on, incandescent with pain over male privilege, violence, impossibility. Morgan says she is “Dying. Going crazy. / Really. No poetic metaphor.” She longs for verbal violence:

Sweet revolution, how I wish the female tears

rolling silently down my face this second were each a bullet,

each word I write, each character my typewriter bullets

to kill whatever it is in men that builds this empire

colonized my very body,

then named the colony Monster.

She struggles with the way women are reduced to silence listening to strange men talk about women, what it means to love the particular men who nonetheless enact “an ornate ritual of what passes for struggle / which fools nobody.” A woman asks her “But how do you stop from going crazy?” and she answers “No way, my sister. / No way.”

There is no resolution, of course, to the struggle the poem recounts – not then, not now. Still, Morgan seeks what can be affirmed in the midst of such impossibility. She turns to her body speaking its pain in hives like stigmata, and imagines turning the power of language to a new creation:

And I will speak less and less to you

and more and more in crazy gibberish you cannot understand:

witches’ incantations, poetry, old women’s mutterings,

schizophrenic code, accents, keening, firebombs,

poison, knives, bullets, and whatever else will invent

this freedom.

It is easy to find the rage melodramatic. If you are white, cisgendered, privileged at least. It seems so archaic to speak so unselfconsciously of revolution, or a woman’s revolution at least. But then, in 2017 it may be less melodramatic than it would have seemed, as revelations of the regular and widespread sexual harassment and terrorizing of women by men in power began to be revealed. It is horror that has been veiled by fear and a conspiracy of silence. #Metoo: women tell their stories. But we are still unsure how to voice it. How to speak as a victim? How to speak with rage? How to speak in a way that is powerful? Always the danger is still becoming monsters. I think of the viral video of actress Uma Thurman from November 2017, who when asked to comment on her view of sexual accusations against producer Harvey Weinstein, responded, “I don't have a tidy soundbite for you, because I've learned -- I'm not a child, and I've learned that when I've spoken in anger I usually regret the way I express myself. So I've been waiting to feel less angry. And when I'm ready, I'll say what I have to say." Probably she was right, in practical terms. Controlled speech is power, yes. But power on another’s terms. Power shot through with fear.

I think of the rage of prophetic speech, of Anne Hutchinson letting go into her truth and ultimately into prophetic fury, even though it would doom her. Of how, in January 1637, John Wheelwright invoked a spiritual violence that for the orthodox who were its target teetered on the edge of literal warfare, the sermon which led to a charge of sedition and ultimately set the court hearings and banishments in motion. Of how, two decades later, the earliest Quakers would write in the transports of encounter with God and of rage and sorrow at their persecution at the hands of those who claimed to be fellow Christians. It was God’s judgment they channeled, but everything they would not say humanly was in claims and cadences, how could it be otherwise. In their language they were not the peaceable people they would later become. In their jumbled, furious writings that break all the rules and sound like nothing but themselves.

After Anne Hutchinson’s banishment, after John Winthrop and Thomas Weld told their version of what happened, thinking themselves victorious (for she was murdered now in a show of divine providence, and all her followers more or less safely fighting amongst themselves in Providence and Portsmouth and Newport) in A Short story of the Rise, Reigne, and Ruine of the the Antinomians, Familists, and Libertines, her brother-in-law John Wheelwright would respond a year later with Mercurius Americanus, in which he attempted to defend her (most half-heartedly, trying to justify himself being by far the more urgent part of his agenda):

As for Mrs. Hutchinson, she was a woman of a good wit, and not only so . . . but naturally of a good judgment too, as appeared in her civil occasions; in spirituals indeed she gave her understanding over into the power of suggestion and immediate dictates, by reason of which she had many strange fancies, and erroneous tenets possessed her, especially during her confinement, where she might feel some effect too from the quality of humors, together with the advantage the devil took of her condition attended with melancholy.

Possessed by strange fancies, beset problematic humors, taken advantage of by the devil. All the defense he would venture: not without gifts but she went kind of crazy. And rightly expelled for her vision of the destruction of the Court. So much more to say on his own behalf, but this was the most her could spare for her. William Dyer would hint at the same thing when his wife, whom he had not seen for half a year, returned to Boston to go to the gallows. Don’t judge her so harshly, she must not be herself. Not the woman I knew and loved. Think of me, a husband like yourselves. Oh men, with all your pleading.

I think of us all now, women and men, struggling for words and expression as we watch everything we hold good being pulled down all around us. Experiencing ourselves as something like a colonized people, our hope of the closest thing to fulfillment of a women’s revolution broken overnight. Not that we don’t need analysis, encouragement, direction. Humor. But still, where is our keening? No wonder clever memes and rational argumentation cannot satisfy us. No wonder so many feel they are going crazy. Maybe we have not yet found our wild language.

The monster is what we fear. The monster will not save us. There is no way forward without the monster.

Morgan’s poem ends:

May we go mad together, my sisters.

may our labor agony in bringing forth this revolution

be the death of all pain.

May we comprehend that we cannot be stopped.

May I learn how to survive until my part is finished.

May I realize that I

am a

monster. I am

a monster.

I am a monster.

and I am proud.

Anne Hutchinson and Mary Dyer were not feminists. The revolution they wanted was something else. But is it too much to imagine that in their way they would have understood this poem?

I think these lines must be this book’s secret epigraph.